Aggregated News

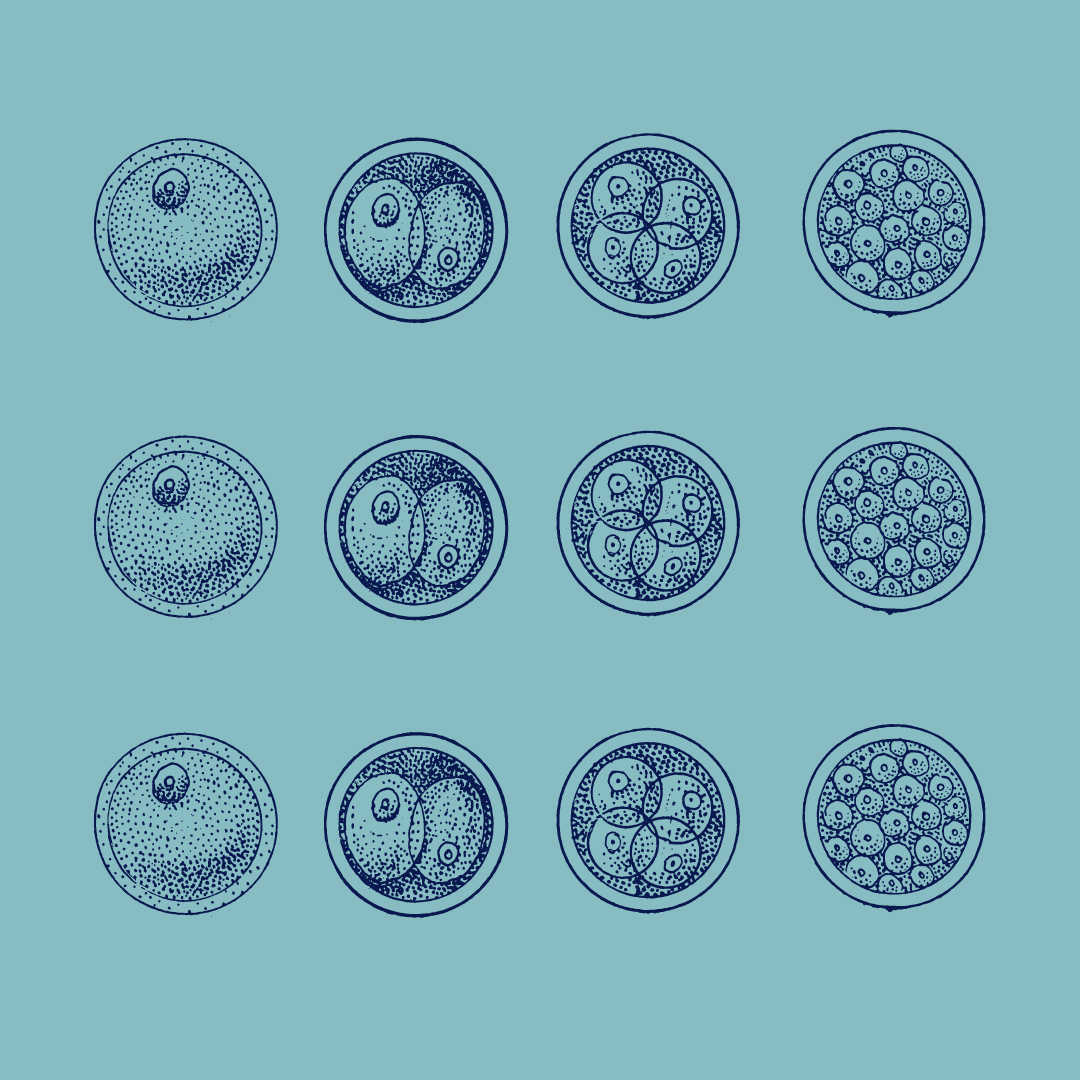

Under his microscope, Jun Wu could see several tiny spheres, each less than 1 millimetre wide. They looked just like human embryos: a dark cluster of cells surrounded by a cavity, and then another ring of cells.

But Wu, a stem-cell biologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, knew that these spheres were not what they seemed. They were laboratory-grown models of embryos, and they were far from perfect replicas.

Entire groups of cells were absent and others were there that didn’t belong. And Wu knew that, eventually, the models would perish abruptly and chaotically.

If embryo models were houses, then behind the facade they would have uneven floors, distorting mirrors and ghosts in their closets. Nonetheless, dozens of labs are competing to grow the best likeness of a human embryo.

There are as many models as there are groups making them, each recapitulating slightly different aspects of embryo development in the hope of uncovering new biology about the first weeks after conception.

This high-stakes, high-drama period “is shrouded in mystery”, says Nicolas Rivron, a...