First UK Babies Born after “Three-Person IVF”: Why all the secrecy?

Adapted from Mitochondrial DNA at

National Human Genome Research Institute

The Guardian reports that “a small number of babies” with DNA from three people have now been born in the UK. The exact number has not been disclosed; it is less than five but more than one. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), the government agency that regulates the process, revealed that much in response to a freedom of information request, and noted in a rather terse statement that “32 patients have been given approval for mitochondrial donation treatment.”

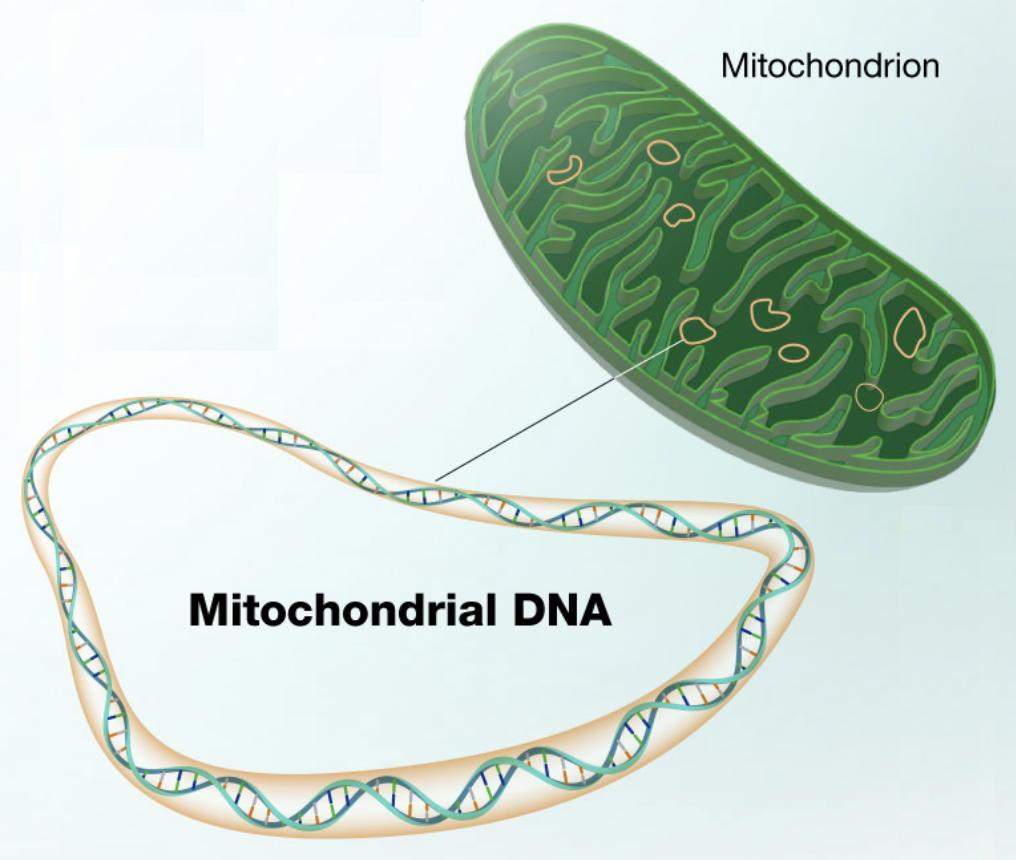

That is the official name for the technique, which is also known as “3-person IVF” or “nuclear genome transfer” (the most technically accurate term). This experimental process is intended to allow women with harmful mutations in their mitochondrial DNA, a tiny subset of the genome, to avoid passing on rare but damaging diseases to their children. (Other scientists and fertility doctors are working on similar techniques that they say will overcome infertility; their approach is speculative and not approved by the HFEA.)

This technology is controversial not only because of its significant safety issues but also because it is a cellular engineering process that is heritable through the maternal line. That is why the National Academies 2016 report, Mitochondrial Replacement Techniques: Ethical, Social and Policy Considerations, recommended that only male embryos be transferred, at least initially, to avoid passing on edits to future generations. For important background, see also this 2017 essay, “3-Person IVF: Putting the First Legal Genetic Modification of Babies in Context” by Jessica Cussins. CGS has noted, in a press release, that these techniques do not treat any existing person for a disease, illness, or condition, and safer options for creating families are already available. Ayesha Chatterjee discussed practical, ethical, and commercial issues in a 2019 post at Biopolitical Times that remains relevant today.

The secretive way in which this controversial research has been conducted raises some disturbing issues. After all, the experiments involve actual pregnancies and babies. There have as yet been no peer-reviewed scientific publications, though according to the HFEA “the team at Newcastle [where this research is being done] hopes to publish information of their mitochondrial treatment programme in peer reviewed journals shortly.”

The HFEA attributes the lack of public information to the need to respect the privacy of the patients involved. But how would describing the results in purely scientific terms encroach on their privacy in any way?

There are many significant unanswered questions, for example:

- How many of the 32 approved patients (or experimental subjects) underwent the procedure?

- How many became pregnant and how many attempts were unsuccessful?

- What was the success rate at each stage of the process?

- Was prenatal testing carried out during the course of pregnancies?

- Exactly how many babies have so far been born?

- Most importantly, are the babies healthy in general, and specifically are they free of mtDNA-related disease?

And perhaps most significantly for the prospect of continuing and expanding this line of research:

- Has there been any evidence of “mtDNA reversal” (or “reversion”), as described in Wells et al.?

This deserves some explanation: When the nucleus of the intended mother’s egg is inserted into the enucleated donor’s egg, a tiny percentage of her faulty mtDNA is sometimes also carried over. Reversion describes a process whereby, for reasons not well understood at all, the few faulty mitochondrial genes from the intended mother wind up multiplying faster than the mtDNA of the donor egg. So an apparently successful procedure may turn out to be surprisingly unsuccessful, after a period of months or perhaps even years. This has been demonstrated by some of the foremost researchers in the field, including David Wells and Shoukrat Mitalipov, using essentially similar techniques as a speculative treatment for infertility thought to be connected with mtDNA. The results of their experiments were described in a recent Biopolitical Times blog post, explained more fully in MIT Technology Review, and documented first in a paper published in Fertility and Sterility:

For 5 of the 6 children, mtDNA was derived almost exclusively (>99%) from the donor. However, 1 child, who had similarly low mtDNA carryover (0.8%) at the blastocyst stage, showed an increase in the maternal mtDNA haplotype, accounting for 30% to 60% of the total at birth.

This result was surprising, and deeply concerning. What does Newcastle know?

The Guardian deserves considerable credit for investigatory journalism. Other outlets followed that lead, but appear to have added very little information. A quick search turns up scores of results from around the world: BBC, AP, The Independent, Daily Mail (which has also been on this story for years), The Mirror, Sky News, NBC, News.com.au (Australia), The Economic Times (India), Al Jazeera, ABC7 New York, BMJ, Healthnews … Editors certainly think there is public interest in these issues.

The Science Media Center, a rapid-reaction nonprofit that aims to improve communication between scientists (whom they generally support) and journalists, compiled reactions from five experts: Peter Thompson, the HFEA’s Chief Executive; Sarah Norcross, Director of PET; the ubiquitous Robin Lovell-Badge; Prof Darren Griffin, a world leader in cytogenetics; and perhaps most interestingly David Clancy, Lecturer in Biogerontology at Lancaster University, who noted the different perspectives and language that people bring to this issue:

The ethical and procedural facets of this whole area are many and fascinating. … Mitochondrial replacement therapy is not really even therapy, and it is certainly not a cure in any regular sense of the word. … Some [countries] consider it to be germline modification. … Nor do I know the extent to which women who carry mitochondria which cause disease are informed of the options to have a child by donor egg, because mitochondrial replacement is a technique whose only advantage is to allow a woman to have a child that is genetically related to her.

Finally, we should note that the small but unknown number of babies purportedly born at Newcastle are not the only such children in existence. The first was born in Mexico, where there was at the time arguably no legal prohibition, on April 6, 2016, and others have been reported in Ukraine and Greece. Very few countries have legalized and defined oversight for the procedure, as the UK did in 2015. (Australia is the process of setting up a system.)

Sunshine, as the saying goes, is the great disinfectant. It is past time for the details of this research to be examined by experts and published for all to see.