Forensic DNA and the “Golden State Killer”

The use of DNA for forensic purposes is long overdue for reassessment. The alleged identification of the so-called “Golden State Killer” (also known by several other nicknames) may just be sparking debates that have been needed for decades, about the law, privacy, databases, and the reliability of DNA evidence.

Details of the methods used to identify the suspect are still emerging; the police have been reluctant to discuss them. We now know that at least one subpoena was issued to a DNA ancestry company, and the AP and several other news organizations have filed a motion to unseal the arrest warrant and the search warrants detectives obtained, citing the public’s longstanding right to access court records and the immense public interest in the case.

It is noteworthy that many news outlets followed up the story of the arrest with articles about concerns, both technical and ethical. The New York Times, for instance:

The Golden State Killer Is Tracked Through a Thicket of DNA, and Experts Shudder

See also The Atlantic, Buzzfeed, STAT, MIT Technology Review, and for both science and ethics, Science News, and particularly Rikki Lewis at Genetic Literacy Project. This suggests that the need for further discussion, and perhaps legislation, is being widely accepted.

One known problem with the present case is that a false identity was concocted to enable access to a public database. That appears to violate the terms of service of the site, and might possibly raise a Fourth Amendment issue, which could make the DNA evidence inadmissible.

So might the use of “abandoned” DNA to confirm the suspect’s match to the rather old sample of DNA left by the killer. The match itself might be challenged by a defense lawyer, given that such identification has proved false in the past. Contamination, flawed systems, and human error are not as unusual as TV fictions suggest.

The heinous crimes involved (at least 51 rapes and 12 murders, mostly dating back to 1976–1981) might make it seem very tempting to overlook any procedural issues if the evidence obtained is strong enough. But, as the old saying has it, justice must not only be done but be seen to be done.

From a broader perspective, we as a society badly need to consider in depth the underlying issues not just of law and technology, but of privacy and how we deal with huge, modern databases — not only of DNA, but of personal health, of finances, friendship, political opinion and much more. Connections between them, such as between criminal and ancestry data, are beginning to proliferate. So too are concerns about racial bias, in particular in police databases where "familial searches" disproportionately affect communities of color.

These debates are only becoming more urgent.

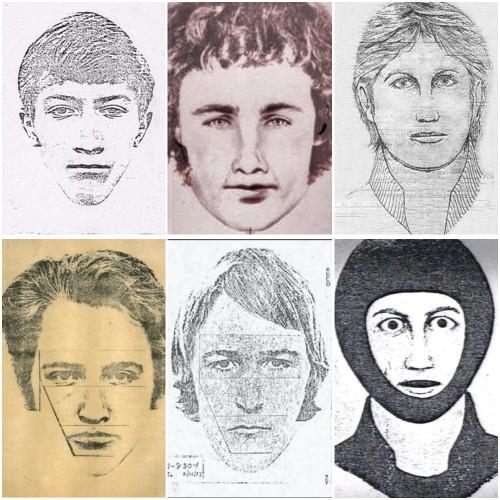

[Police sketches via wikipedia]