How Can We Assess Public Opinion?

Image by Avopeas, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

It is a truth almost universally acknowledged that it would be irresponsible to perform heritable human genome editing – that is, to engineer the genes and traits of future children – unless and until “there is broad societal consensus about the appropriateness of the proposed application.” But how would we know if that goal had been achieved?

The only way to determine this would be through a robust process of public deliberation. Professional scientists and bioethicists have certainly been engaged in discussions, but many other interested parties, notably civil society organizations committed to social equity and justice, have generally not been included. As discussed in the Geneva Statement, by a distinguished group of public interest advocates, policy experts, bioethicists, and scientists, including CGS’s Marcy Darnovsky, Katie Hasson and Osagie K. Obasogie, there is an urgent need for course correction in such a process. For instance, it is vitally important to:

- clarify misconceptions;

- center societal consequences and concerns;

- and foster public empowerment.

Some kind of survey process might also be helpful. But it can’t be one that relies on the false assumption that using gene editing in human reproduction will inevitably become safe and effective, as is sometimes posited. Even when these assumptions are stated as hypotheticals, they distort rather than foster public understanding and informed decision making. Moreover, asking respondents to bracket considerations of safety and effectiveness can also imply that other concerns – about the effects on families, communities, and societies, for example – are less fundamental.

On the other hand, we shouldn’t wait to see whether a scientific consensus about safety and efficacy emerges before we begin to probe public opinions about whether heritable genome editing should be pursued. For one thing, the public does pay for a large amount of the research and deserves to be consulted in some way and to some extent about the allocation of resources. Scientific work to establish safety and efficacy of heritable genome editing should not be able to sidestep the question of whether this application should be pursued at all. Politicians have a broad responsibility for this; civil servants administer the details; and public attitudes are certainly relevant.

Three approaches are considered here, none exactly on the topic of human genome editing, heritable or otherwise, but all recent and on related topics. One is longitudinal, over more than 20 years; one attempts to be educational for a focus group but seems to put a hefty thumb on the scale; and another focus group offers complex responses that question the value of technological responses to human problems.

The Annual Gallup Surveys

A classic – and resource-intensive – method of gauging opinion is to watch how it develops over time. The Gallup Organization, one of the few with the resources and history to do this, has conducted the Gallup Poll Social Series since 2001, “to monitor U.S. adults’ views on numerous social, economic, and political topics.” (Some of the trends analyzed go back much further in time, some not quite as far.) Every May, the topic is Values and Beliefs, which covers 19 specific issues. In each case, the question is:

Regardless of whether or not you think it should be legal, for each one, please tell me whether you personally believe that in general it is morally acceptable or morally wrong.

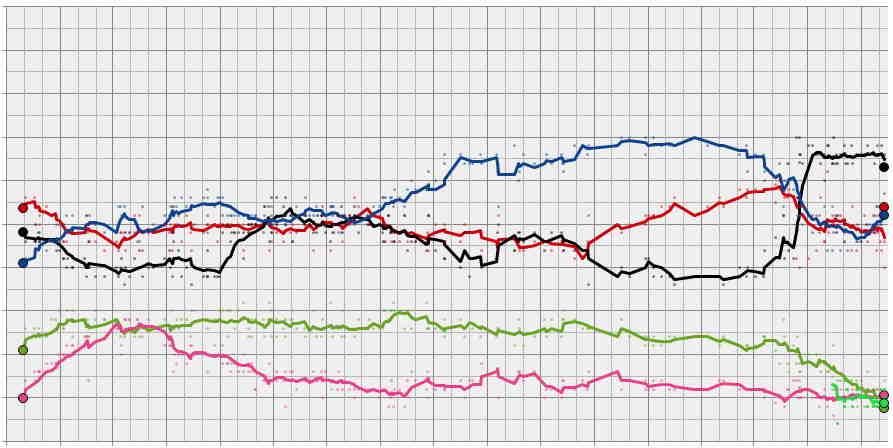

A few results from the Gallup “Moral Issues” page, each showing the percentage of respondents that considered a topic morally acceptable, in the 2002, 2012, and 2022 surveys:

Divorce: 63 – 67 – 81

Gay or lesbian relations: 38 – 54 – 71

Stem cell research using human embryos: 52 – 58 – 63

Abortion: 38 – 38 – 52

Cloning animals: 29 – 34 – 38

Cloning humans: 7 – 10 – 11

Married men and women having an affair: 9 – 7 – 9

There have been some fluctuations in the data over two decades but in general the results follow clear trends. The approval ratings of divorce, gay or lesbian relations, and abortion are at all-time highs. The other topics have occasionally nudged a point or two higher than in 2022, probably within the margin for error.

Clearly, Americans have become much more accepting of gay and lesbian relations over the past two decades, and significantly more tolerant of both abortion and divorce. Human cloning might be better described as a little less unacceptable today than 20 years ago – certainly there is no “broad social consensus” in favor of it. “Stem cell research using human embryos” has become somewhat more acceptable, but the question as posed is rather out of date, given scientific developments in the stem cell field.

Does Gallup suggest that there is now or soon will be broad societal consensus about the appropriateness of heritable human genome editing? Clearly not. Without specific additions to the questionnaire, we cannot even be certain about the extent to which public opinion on the topic is evolving, if at all.

Gene Drives in Australia

Australia has enormous environmental problems, as its government well knows. A major report was scheduled for 2021 but publication was delayed by six months until after a general election, which the incumbent government lost decisively. In addition to climate change, which is an extremely important topic in Australia, the environment has been enormously affected over generations by animal pests such as cats, rabbits, foxes and pigs, all (and many more) introduced deliberately or accidentally, to the detriment of native species.

One proposed solution involves the use of synthetic biology and gene drives to remove the invaders. But would the public accept this technological approach? The Australian national science agency CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) conducted a survey of 3,823 Australians and published a glossy report about it on June 20, 2022 (pdf). The survey included an educational animation to explain gene drive technology, and even asked whether participants believed the animation was biased in favor of gene drive; participants thought it was, with an average response of 3.78 out of 5. The report deserves some credit for including that.

The public certainly agreed that pest species are a problem: 77% considered them an extreme or high threat to natural biodiversity and most of the rest called the threat moderate. Very few people knew much about synthetic biology (2% claimed extensive knowledge and another 7% a lot) but 66% were supportive or very supportive of using synthetic biology to solve problems in environmental conservation. Moreover, 89% supported with various levels of enthusiasm the development of gene drive technology for pest control (after being instructed on the topic by the science agency).

The survey did, however, elicit some apparent contradictions, which the CSIRO report characterized as “mixed views … about whether humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs”:

Science can provide solutions to environmental problems:

Strongly agree 50%; agree 38%; neither 7%; disagree 1%; strongly disagree 3%When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences:

Strongly agree 31%; agree 45%; neither 19%; disagree 5%; strongly disagree 1%

Is that paradoxical? Or perceptive?

The Australian government may use these responses to claim a green light to proceed with gene drives. But skeptics and opponents can certainly attack the report as biased. And that line about “disastrous consequences” may have resonance in any future public debate.

Learning from the West Bromwich African Caribbean Resource Centre

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is conducting an in-depth inquiry into “The future of ageing” and recently posted a report by Molly Gray on one particular day-long focus group. This was conducted at a Resource Centre in the English midlands, near Birmingham. All the participants were 75 or older, and of African Caribbean origin.

The group demonstrated a focus on social connections and practical matters of housing and transport. They demonstrated skepticism about technology, specifically about “the profit and competition motives of pharmaceutical companies,” and advocated for “regulation and appropriate testing of future technologies.” The workshop ended with discussion based on this question:

“If you had £10 million, what areas should be prioritised for investment in healthy ageing?”

Many factors were discussed, but what most struck the reporter was this:

Interestingly, few people felt additional funding should be spent on developing new technologies, but rather most talked about the need to direct large amounts of money for the “greater good” and “to those who need it more”, referring both to people from lower socio-economic backgrounds and developing nations.

The wisdom of old age?

The Need for Nuance

Any kind of polling suffers from the perfectly understandable tendency to simplify issues, and should be interpreted with care. The wise old people in the Nuffield study, who were skeptical about the value of investing in expensive technologies to help them, chose instead to help others. They did so in what seems to have been a context of trust developed over hours, which included sharing food. Also, they expressed that view in response to an essentially open-ended question about how resources should be allocated. If the poll had listed a series of options for spending the money, would “I have a better idea” have been one?

Similarly, it was a little unfair to make the Australians seem to contradict themselves so blatantly: the divergent responses about “science providing solutions” versus “disastrous consequences” of interfering with nature appear to have been elicited in quite different contexts. In the report, the “disastrous” comment directly follows this:

Humans have the right to modify the natural environment to suit their needs

Strongly agree 4%; agree 24%; neither 31%; disagree 29%; strongly disagree 12%

If that was the sequence in which the survey questions were posed, then the concept of “disastrous consequences” might seem less of a stretch.

Returning to the topic of heritable human genome editing, similar pitfalls always need to be avoided. Examining the many polls collected by CGS, it is striking how often the questions follow a sequence, such as (from a 2022 YouGov poll in Britain): “Would you approve of using gene editing to … change people’s appearance? ... change their future children’s appearance? ... make people more intelligent? ... make their future children more intelligent?” The sequence appears to lead the respondent to an answer (“If you don’t like a vivid red, can I interest you in a soft pink?”), even if that is not the intent. That of course is why some polls randomize the order in which questions are posed, but not all do.

There can also be problems of omission. For instance, questions about eugenics, in its emerging, modern, technology-based form, are rarely raised. Of course, the word itself has rightly accrued opprobrium, but consideration of broader social effects than merely those on particular individuals or families certainly deserves serious consideration. This is not an easy task. Pew found, in an unusually detailed 2021 survey, that respondents thought that gene editing would “would pave the way for medical advances that benefit society as a whole” (67–30) but also “would go too far eliminating natural differences between people in society” (68–29) – a pair of results that cries out for discussion.

Scientists who are over-enthusiastic about “improving” families through genetic engineering may well discover that the public at large is revolted by the prospect. But we’ll never know unless we can devise better ways of asking.