A Monkey Circles in a Cage

Monkeys with Autism?

“…first ever nonhuman primates to show autism-like symptoms in the lab.”

On January 25, news broke widely in the press on research published in Nature by a team in Shanghai, who spent six years creating two generations of macaque monkeys engineered to have duplications of the MECP2 gene in their brains—a gene that researchers have associated with Rett Syndrome, a condition on the severe end of the human autism spectrum.

|

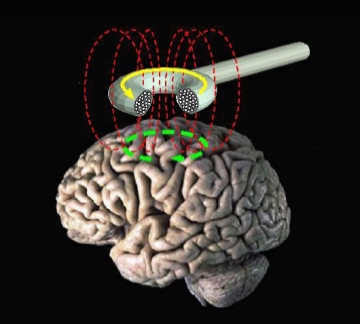

The researchers listed a battery of behavioral tests which they claimed as evidence that the transgenic monkeys were now genetically predisposed to autism-associated behaviors. In a press briefing organized by Nature, Zilong Qiu, a leader of research at the Institute of Neuroscience at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, stated plans to leverage their research into human clinical trials down the line, with the aim of developing somatic gene therapies or non-invasive interventions like trans-cranial magnetic stimulation [Wiki] to correct autism in humans. Qiu stated the researchers are currently trying to identify the brain circuitry responsible for what they believe is the monkeys' changed, autism-like behavior; after that, they plan to use CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to manipulate the MECP2 duplications in the transgenic monkeys they created. |

|

With “autism,” “transgenic,” and “monkey” in the headlines, it’s not surprising that a flurry of media coverage might flatten the social and ethical implications of what’s at stake with using animals models to study stigmatized human behavioral conditions. One article was promoted on Twitter as “First Monkeys with Autism are Sickly Loners Who Pace Their Cages.” Comments on that article included: “I have a child with autism and even I find what you are doing to these monkies [sic] repulsive. This is a sad commentary on science and our society.” …“I have a daughter with autism, and I find this to be very disturbing!!!” … “I'm autistic, but I don't need to be cured, thank you very much.”

The Limits of Animal Models in Studying Human Behavior

While unvalidated claims that vaccines cause autism are ongoing, scientists have been motivated for some time to clarify genetic bases for autism spectrum disorders. Some estimate that hundreds of genes are involved, many assert that environmental factors may also be at play, and many others assert that the majority of “disorders” classified as autism (and targeted by market-driven drug trials) are just points on the spectrum of human neurodiversity that we ought to be de-stigmatize and de-medicalize.

Most articles on the transgenic monkeys cited scientists who agree that cheaper, quicker mouse models have severe limitations in studying human behavior. Yet a number of reporters, or the scientists they quoted, pushed back on the claims of the study. David Cyranoski in Nature quoted stem cell and autism researcher Alysson Muotri, who stated that symptoms in mice and monkey animal models for autism are often “less severe than ‘what we actually observe in human patients… It remains to be seen if the model can actually generate novel insights into the human condition.’” James Cusack, research director at Autistica, told Ian Sample in the Guardian that “people with autism vary in a number of ways, and autism itself is linked to a number of other conditions. With this in mind, developing a single animal model of autism may be difficult to achieve.” A number of reporters also cited MECP2 pioneer Dr. Huda Zoghbi’s critiques of the study, including: (1) the monkeys did not exhibit behaviors associated with MECP2 duplication in humans like seizures and severe cognitive problems; (2) the monkeys’ circling behavior in their cages is a symptom not exhibited in human children with MECP2 duplications (perhaps the cage is relevant); and (3) the monkeys only carried MECP2 duplications in their neurons, not throughout the brain as in humans with Rett Syndrome.

The Ethics of Biomedical Research on Animals

Virginia Hughes in BuzzFeed discusses the pulse of clinical research moving from mice toward sentient non-human primates,

.jpg) |

linking to the recent debut of transgenic monkeys with a 2008 US study on the genetics of Huntington’s disease. The first transgenic monkeys made with CRISPR-Cas9 were reported by researchers in China in 2014. Hughes notes that research with non-human primates is “ethically fraught”; indeed the ethical pushback to genetic experimentation on monkeys and other animals is wide-ranging in recent news:

|

- In BuzzFeed, Hughes links to the extensive and compelling reporting done by Peter Aldhous on the use in the US of thousands of monkeys, many of whom were killed, in testing experimental drugs for biosafety research in the “war on terror” (July 2015).

- A recent memo by Francis Collins was leaked stating that the NIH is effectively ending its support of research on chimpanzees (November 2015), following a decision by the Fish and Wildlife Service that chimpanzees are an endangered species (June 2015).

- The NIH also placed a ban on funding of animal-human chimeras created by introducing human pluripotent stem cells into vertebrae animal embryos (September 2015), an area of research moving forward in the private sector to study xenotransplantation (January 2016). Many, including the NIH, the National Academy of Sciences, and CGS Senior Fellow Osagie Obasogie writing in the San Francisco Chronicle in 2006, have noted such research may lead to an uncanny ethical valley of humanness in hybrid organisms.

- Researchers are using CRISPR to edit the horns off of cows pre-birth to make them more convenient for Big Ag (December 2015), amid “a flurry of research looking at how to make cattle easier to maintain, transport and turned into food” despite “concerns among some farmers and animal-rights activists.”

- Cover-ups in Australia of ongoing experiments on baboons and other primates costing taxpayers millions of dollars were recently reported, involving research aimed at developing human treatments and xenotransplantation (January 2016).

- Animal cloning factories are in the news, including in China, with a range of customers, including sentimental individuals with dead pets, military and police forces, and big agriculture; and with the stated organizational goal of migrating into human cloning experiments. Then there’s the “Google”—err—Monsanto “of life sciences” being erected by technoenthustiastic but venture capital-allergic billionaire Randal Kirk, which Pete Shanks outlines in detail in Who Will Pay for Human Germline Changes?

In just the last few months, this evidence shows a growing swath of concerns regarding animal research ethics that the biomedical sector will encounter as it moves forward with monetizing CRISPR gene editing and placing clinical applications in the research and development pipeline.

Previously on Biopolitical Times:

- The Third Rail of the CRISPR Moonshot: Minding the Germline

- The CRISPR Germline Debate: Closed to the Public?

- What Will 120 Million CRISPR Dollars Buy?

Image via Flickr/Vince O'Sullivan