Some Recent and Forthcoming Books on Human Genome Editing

“Another damned thick book! Always, scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh, Mr. Gibbon?”

— The Duke of Gloucester, on being presented with Volume 2 of

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

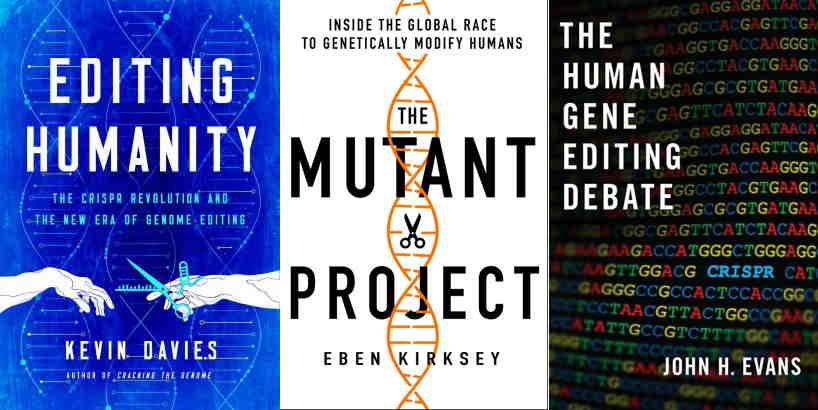

Several titles have caught our attention lately, three published in the past few weeks and two more announced for early 2021.

Already published:

- Kevin Davies, Editing Humanity: The CRISPR Revolution and the New Era of Genome Editing, published October 6, 2020 (Pegasus Books). Davies is the editor of The CRISPR Journal, and in 2010 published The $1,000 Genome: The Revolution in DNA Sequencing and the New Era of Personalized Medicine. The new book was reviewed, perhaps a little more peevishly than necessary, by Carl Zimmer in The New York Times.

Unsurprisingly, Davies opens with the He Jiankui fiasco — the Chinese scientist who achieved infamy when he announced in late 2018 that he had gene-edited human embryos and brought to term two babies.

- John Evans, The Human Gene Editing Debate, published September 1, 2020 (Oxford University Press). Evans has been writing about this for at least two decades, having published Playing God? Human Genetic Engineering and the Rationalization of Public Bioethical Debate in 2002. His latest does not yet seem to have generated the attention it may deserve, possibly because it’s the most scholarly of the bunch.

For a preview, see the article Evans posted at the OUPBlog, titled “The slippery slope of the human gene editing debate.” That post does not specifically mention He Jiankui, but the first sentence of the new book does, though not by name, merely as “a Chinese scientist.”

- Eben Kirksey, The Mutant Project: Inside the Global Race to Genetically Modify Humans, November 10, 2020 (St. Martin’s Press). This could be very interesting: The publisher lists blurbs by many distinguished people, including Dorothy Roberts (CGS Advisory Board member), Agustin Fuentes, and Alondra Nelson.

We haven’t had time to read it all yet, but note that the book’s Prologue is focused on the way He Jiankui “put the world on notice.”

Coming early next year:

- Hank Greely, CRISPR People: The Science and Ethics of Editing Humans, due February 16, 2021 (MIT Press). The prolific Stanford Professor of Law and Genetics (the latter by courtesy) published The End of Sex and the Future of Human Reproduction in 2016. Then, he focused on embryo selection (and was generally unworried) but the debate is now about human germline editing, for which he sees “very few good uses.”

The publisher’s web page features a blurb from Antonio Regalado, and a Summary that focuses entirely on He Jiankui, whose experiment Greely regards as “grossly reckless, irresponsible, immoral, and illegal.”

- Walter Isaacson, The Code Breaker: Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race, due March 9, 2021 (Simon & Schuster). The indefatigable biographer (Kissinger, Franklin, Einstein, Jobs, Da Vinci) risks falling into a personality trap, but his reporting is usually sound, and Doudna’s recent Nobel Prize won’t hurt. His book has attracted pre-publication praise from Jon Meacham, Doris Kearns Goodwin, and others.

(Just a guess, but this one is probably more likely to open with Doudna’s Hitler dream than with you-know-who.)

Unsurprisingly, most of these new books lead with a focus on the Chinese scientist He Jiankui, who has become something of a pantomime villain. This high drama approach is no doubt effective as a narrative hook, and it highlights one set of problems we face. But does it obscure what’s fundamentally at stake in the debate about heritable genome editing? Does it distract from issues of policy and values; of individual and collective responsibility; of authority and regulation in a multinational world with many intersecting and sometimes conflicting interests?

All these books seem very much worth reading. It will be interesting to do so with those questions in mind.