Why the Newest Lindbergh Baby Conspiracy Theory Isn’t All That Out There from a Disability History Perspective

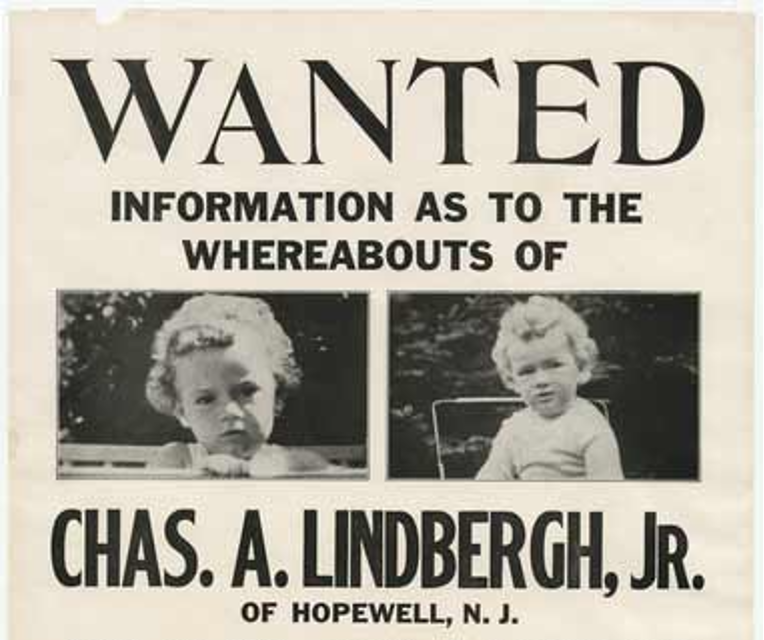

The 1932 kidnapping and murder of Charles Lindbergh’s 20-month-old son was called the “crime of the century” at the time, and has inspired more and less plausible theories about what really happened ever since. The San Francisco Chronicle has recently covered a new wave of interest in the case, based on retired judge Lise Pearlman’s 2020 book that builds on a theory that’s been around for decades: that the celebrity aviator himself was implicated, and the man executed for the crime was in fact innocent.

While I’m not typically one to dabble in conspiracy theories, Pearlman’s claims pull me in for two reasons. First, they bring to light an important part of Lindbergh’s story that few of us learned in school when we read about his celebrated cross-Atlantic solo flight: he was an anti-semite, Hitler sympathizer, and proponent of eugenics. Second, Pearlman’s ideas have chilling implications for disability history.

A new twist on an old theory

On March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was allegedly kidnapped from his nursery. The days that followed involved a complex web of clues, the pursuit of leads that led nowhere, negotiations following 12 ransom notes (experts determined that all were written by the same person, of German descent), and one payoff to an anonymous man named “John.” The discovery of the deceased child’s body over two months later less than five miles from the Lindbergh home opened more questions and uncertainties.

A high-priority investigation eventually led to the arrest of Bruno Richard Hauptmann in 1934 after he cashed in some of the gold certificates traced back to the ransom. Hauptmann maintained his innocence yet was electrocuted in 1936, and his descendents have continued to fight to clear his name, with recent support from the Innocence Project.

As with any high-profile case, conspiracy theories spread through the zeitgeist. Many doubted the evidence linking Hauptmann to the kidnapping and murder from the start. Almost a century later, scrutiny of the Lindbergh baby case hasn’t faded.

Pearlman proposes what the San Francisco Chronicle calls “a new, macabre theory about the case: that Lindbergh offered up his child as a subject for medical experiments and faked the kidnapping to cover up the child’s death.” Given evidence that the boy was “known to be sickly and to have an abnormally large head,” she argues that Charles Lindbergh allowed him to be used for medical experimentation by his close colleague, fellow eugenicist and Nobel Prize-winning French biologist Alexis Carrel. Lindbergh was working with Carrel in research on techniques for organ transplants (underlying this work was Carrel’s desire to preserve the “white race” from “less intelligent stock” – see Marcy Darnovsky’s 2010 post to go down Carrel’s rabbit hole).

Even if Pearlman’s theory is true, she of course has no way to know whether Lindbergh wanted to “normalize” his son, or simply saw the child as disposable due to his disability. She argues that the boy died as a result of a failed experiment, and the kidnapping was a cover-up.

What the Lindbergh case reveals about disability history

Without needing to dive any deeper into the evidence trail that seeks to incriminate Lindbergh, we can take this theory as an opening for a much-needed conversation about disability history. In my view, if that reckoning takes place because of a decades-old obsession with “what happened to the Lindbergh baby,” so be it.

In the 1930s, eugenics was a mainstream movement. It was admired and supported by major US institutions and universities, from the American Medical Association to the New York Times to prominent philanthropists. Despite efforts to sweep this history under the rug after Nazi Germany showed where eugenics could lead, eugenics was a respected pursuit. It was not considered pseudoscience.

If you had a child with a developmental disability, making them disappear was standard protocol. Sometimes this happened by withholding treatment. In 1973, two doctors announced that “of 299 deaths in the special care nursery of the Yale-New Haven Hospital between 1970 and 1972, 43 (14%) were associated with discontinuance of treatment” by medical professionals who had deemed their lives less worthy due to disabling conditions. Other times this happened by geographic isolation, sending children off to “schools,” “colonies,” or “hospitals” that physically extracted them from society and hid them away in under-resourced, overpopulated institutions where no rehabilitation was possible and whole lives passed by in a bed or cage-like crib. Many sterilizations occurred to prevent disabled people from having children, with California performing the highest number of any US state.

And experimentation on disabled people happened too. In Nazi Germany, the Aktion T4 campaign developed the lethal gas chambers by testing them on disabled Germans from asylums. In the US, well after World War II, over 50 children with developmental disabilities at the Willowbrook State School were infected with hepatitis to study the effects of treatment methods to develop a vaccine.

So could a father have offered up his own son to be a medical guinea pig, resulting in the child’s death, and then staged an elaborate cover up? Absolutely. That’s just how stigmatizing it was to have a child with a disability in the 1930s. Add the fact that this father spoke about preventing the breeding of people with lower intelligence and suddenly the “conspiracy theory” doesn’t feel so bananas any more. It feels possible and very heartbreaking.

What the case tells us about eugenics today

Lindbergh, Carrel, and their friend and fellow eugenicist Henry Ford were part of their era’s science and tech elite interested in preserving the “master race” from being diluted by those with “lesser intelligence.” Yet, they all were praised as heroes; each appeared on a cover of Time magazine, for example, though Lindbergh later fell from grace for never refuting his early praise of the Nazis.

Prominent eugenic ideas paired with hefty investments in a quest for immortality by the wealthy tech titans of the day – sound familiar? Jeff Bezos, Ray Kurzweil, Peter Thiel, and many other tech leaders have funded efforts aimed at preventing aging, arguing that immortality is in reach. It seems that the biggest social problem haunting these leaders is their future destiny to die like everyone else. They are determined to buy their way out of it.

Other tech elites like Elon Musk, who is less subtle than others about his eugenic ideologies despite having a disability himself, are focused on the “pronatalist” route, which advises that the smartest among us need to have more kids to protect the future of humanity. Musk has eleven children. And there’s no better example than Musk to help raise the question of whether “smart” is really the best metric for guiding the future of humanity.

If the Lindbergh baby continues to capture public attention, then maybe the clues to understanding this past require looking at our present. And maybe what we need to be asking is whether being a tech celebrity fuels the god complex that drives someone to eugenics, or if it’s the other way around?

Emily Beitiks is Interim Director of the Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability at San Francisco State University.