"Woolly" is a Relentlessly Optimistic Book about De-Extinction

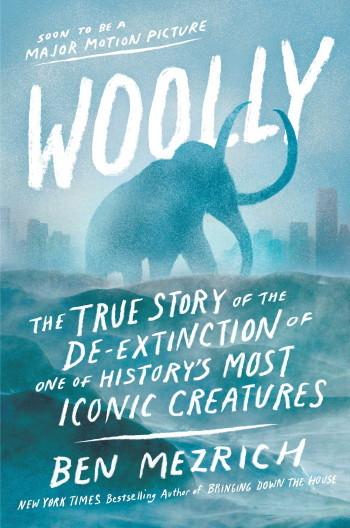

Woolly: The True Story of the Quest to Revive One of History’s Most Iconic Extinct Creatures, by Ben Mezrich; 256 pp. plus Epilogue by George Church, Afterword by Stewart Brand, and endmatter. Atria Books, 2017

The style of Woolly is taken directly from thrillers. It’s a fast-paced romp around the world — Boston, Siberia, Korea, Canada, Florida, California — in 29 short chapters, each introducing a new plot twist. But it ultimately fails even on those terms, because the Quest remains tantalizingly unfinished.

Author Ben Mezrich is certainly a competent professional. He has sold some 30 million copies of close to 20 books, and has been named one of Hollywood’s 25 Most Powerful Authors. Woolly summarizes the science involved in proposals for “de-extinction” fairly well, if briefly. But Mezrich hobbles himself by focusing on a few personalities, notably George Church. A naive reader would get the impression from this book that Church almost single-handedly launched the Human Genome Project and pioneered gene editing with CRISPR. Yes, he was definitely involved in both early on, but both would certainly have happened without him.

The omissions do simplify the story, but at a considerable cost to reality. Jennifer Doudna gets one brief mention as a (pointedly not the) developer of CRISPR/Cas9, but her then-scientific partner Emmanuelle Charpentier is entirely absent. Robert Lanza probably deserves a mention for his part in developing the cloning of endangered or extinct animals. Perhaps most egregiously, Stewart Brand gets all the credit for trying to revive the passenger pigeon while Ben Novak, who had the idea and has been doing the work, is not mentioned.

The book is relentlessly optimistic about the prospect of reviving the mammoth; more so, in fact, than Church, who is generally careful to talk about “neo-mammoths” or “hybrids” which he freely admits would be essentially elephants whose genes had been altered to include a few mammoth traits. Mezrich, however, dedicates the book to his children, “who will grow up in a world filled with Woolly Mammoths.”

There are plenty of environmental, animal welfare, resource allocation, and other arguments against attempts at de-extinction. They are mostly ignored in this book. But there is a fairly detailed discussion about the purported benefits of lowering the temperature of Siberian permafrost, to combat global warming. Experiments in those regions have suggested that the introduction of large mammals might help, but Mezrich gives the game away when he describes the reactions of Church, Brand, and Ryan Phelan (Brand’s partner) to a briefing on the subject:

The Russian scientist had just given them their reason to resurrect their species.

In other words, they were looking for an excuse. They just want to do it. Some of us don’t.

We may not have heard the last of this novelistic almost-nonfiction. There on the cover, right up top, is the ominous phrase, “soon to be a major motion picture.” Mezrich wrote the books that became 21 and The Social Network, so he has the connections. But how do you pitch this one?

Marvel at the eccentric genius of George Church! Gasp as the big truck full of elks skids out of control on the permafrost! Wonder at stem-cell fraudster Hwang Woo-suk’s drive to revive and restore his reputation! Cheer for the young post-docs with their desperate poverty and their enormous intellects!

I see Tom Hanks with a great big beard. Charlton Heston is extinct.

The end of the book – the only part that’s clearly acknowledged as departing from the title’s claim about a “true story” – is dated “three years from today.” It describes the awe felt by Nikita Zimov, a Siberian scientist who is one of Woolly’s recurring characters, “as the fog began to clear, as the shape grew solid and real …”

The Quest is more fantasy than “true story.” But Mezrich covered that just a few pages earlier, when he closed the antepenultimate chapter:

Church always had his feet in both the present and the future, and only he knew for sure which was reality, and which was still just a dream.

Or, of course, a nightmare.

Previously on Biopolitical Times: